Comprehensive Report on the Alavanyo–Nkonya Peacebuilding Project (2013–2015)

By: Youth for Peace and Security – Africa (YPS-Africa)

- Background and Context

The conflict between the people of Alavanyo and Nkonya, located in the Volta Region of Ghana, is one of the longest-standing communal conflicts in the country. Rooted in a land dispute dating back to the late 19th century, the hostilities between these two neighboring communities persisted for well over a century.

Repeated violent clashes resulted in loss of lives, destruction of property, displacement of families, economic disruption, and social fragmentation. Despite multiple interventions by state authorities, security agencies, and religious leaders, a sustainable peace remained elusive.

By the early 2010s, the situation had escalated to a point where both communities had entrenched positions, and mutual distrust was deep. The youth, often manipulated by political or local actors, became central drivers of violence. At the same time, women and children bore the heaviest burden of the conflict, living in constant fear and insecurity.

Recognizing the urgency, Youth for Peace and Security – Africa (YPS-Africa) launched a grassroots initiative aimed at fostering reconciliation, dialogue, and community-led peacebuilding. This project became a turning point in the peace process.

- Project Title and Duration

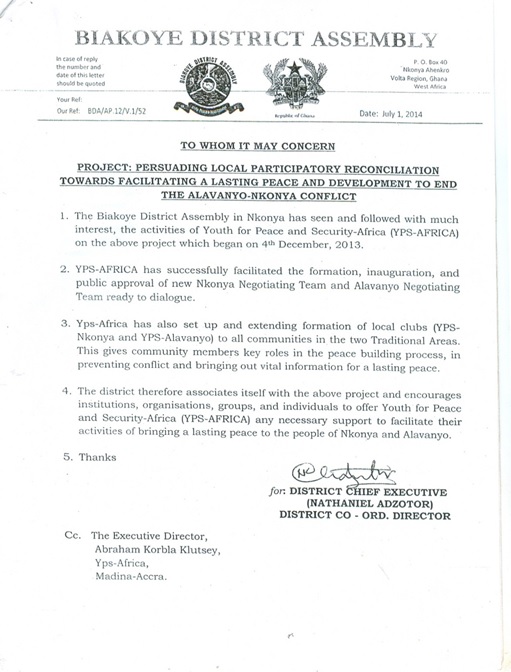

Project Title: “Persuading a Local Participatory Reconciliation Towards Facilitating a Lasting Peace and Development to End the Alavanyo and Nkonya Conflict.”

Duration: December 2013 – January 2015 (14 months)

Lead Organization: Youth for Peace and Security – Africa (YPS-Africa)

Project Leader: Abraham Korbla Klutsey

- Objectives of the Project

The project was designed with both immediate and long-term objectives:

Immediate Objectives

- To create platforms for open dialogue between leaders and community members of Alavanyo and Nkonya.

- To build trust and reduce tensions through inclusive and participatory reconciliation efforts.

- To engage and mobilize the youth as peace agents instead of perpetrators of violence.

- To involve women, traditional authorities, and religious leaders in shaping peace strategies.

Long-Term Objectives

- To transform the conflict from violent confrontation into peaceful coexistence.

- To institutionalize mechanisms within both communities for conflict prevention, resolution, and management.

- To lay the foundation for socio-economic development through sustained peace.

- To create a replicable model of community-led peacebuilding in Ghana and across Africa.

- Methodology and Approach

The project was guided by participatory, inclusive, and grassroots-oriented approaches, focusing on local ownership of the peace process. Key strategies included:

- Community Dialogue Forums – safe spaces were created where community leaders, youth, women, and religious figures could express grievances, share perspectives, and negotiate solutions.

- Confidence-Building Measures – organizing joint cultural events, sports activities, and inter-community visits to rebuild trust.

- Capacity Building Workshops – training youth and women in peacebuilding, mediation, and conflict resolution skills.

- Engagement of Chiefs and Elders – leveraging the authority of traditional leaders to influence community behavior and support reconciliation.

- Partnership with Security Agencies and Religious Institutions – ensuring neutrality, credibility, and security for the peacebuilding activities.

.

- Outcomes and Achievements

The project delivered remarkable results that have endured for more than a decade:

- Cessation of Violent Clashes: By 2015, violent confrontations had drastically reduced, and incidents of open hostilities ceased.

- Sustained Peace: Over 12 years later, the peace remains intact, guarded by local communities themselves without reliance on external peacekeepers.

- Youth as Peace Ambassadors: Former perpetrators of violence became peace advocates, actively discouraging violent responses and promoting dialogue.

- Community Structures for Peace: The establishment of peace committees and peace clubs institutionalized the culture of non-violence.

- Improved Relations: Social interactions between the two communities increased, with intermarriages, joint markets, and cooperative activities gradually resuming.

- Economic and Social Benefits: Farmers could return to their lands, children returned to schools safely, and local markets revived, contributing to socio-economic development.

- Replicable Peace Model: The project became one of Ghana’s most successful community-led peacebuilding initiatives, demonstrating how grassroots approaches can solve deep-rooted conflicts.

- Challenges Faced

Historical Trauma: The century-long animosity meant that initial trust-building was extremely difficult.

Political Interference: Some actors attempted to exploit the conflict for political gain.

Resource Constraints: Limited funding hindered the scale and speed of implementation.

Security Risks: Team members and participants faced threats from extremists within both communities who opposed peace.

Despite these challenges, persistence and local participation ensured progress.

- Lessons Learned

- Local Ownership is Key: Peace that is community-led is more sustainable than peace imposed externally.

- Youth Engagement is Critical: Empowering young people transformed them from “fighters” into protectors of peace.

- Inclusivity Matters: Women, elders, and religious leaders must be engaged equally for peace to take root.

- Dialogue over Force: Lasting peace cannot be achieved through military presence alone,it requires hearts and minds to shift.

- Consistency Builds Trust: Frequent, transparent engagements gradually broke down mistrust and suspicion.

- Sustainability and Current Status

As of 2025:

Local peace committees remain active in mediating disputes and preventing escalation.

Youth and women leaders continue to champion peace through schools, churches, and community associations.

The project has become a reference model for peacebuilding in Ghana, inspiring interventions in other conflict-prone areas like Bawku.

- Conclusion

The Alavanyo–Nkonya peacebuilding project stands as a historic achievement in Ghana’s conflict resolution efforts. It not only ended a century-old communal conflict but also provided a blueprint for grassroots-led peacebuilding across Africa.

Through courage, persistence, and genuine community participation, YPS-Africa under the leadership of Abraham Klutsey demonstrated that peace is possible, even in the most entrenched conflicts.

The story of Alavanyo and Nkonya is now more than history; it is a living testimony that when communities are empowered, peace can be achieved, nurtured, and sustained for generations to come.